- Services

- Artificial Intelligence Development

- Deep Learning & Neural Network Development Services

- Professional Machine Learning Development Services

- Enterprise Computer Vision Development Services

- Enterprise Natural Language Processing Development Services

- Chatbot & Conversational AI Development Services for Business

- Enterprise Computer Vision Solutions For Healthcare

- Transformative Healthcare AI Development

- Retail & E-commerce AI Solutions for Personalization & Growth

- AI Integration & MLOps Development Services

- AI Agent Development & Intelligent Automation

- Generative AI Solutions

- Outsourced Product Development

- Custom Software Development

- Software Customization & Integration

- Mobile App Development

- Custom Application Development

- Software Architecture Consulting

- Enterprise Application Development

- AI-Powered Documentation Services

- Product Requirements Document Services

- Artificial Intelligence Development

- Industries

- Healthcare Software Development

- Telemedicine Software Development

- Medical Software Development

- Electronic Medical Records

- EHR Software Development

- Remote Patient Monitoring Software Development

- Healthcare Mobile App Development Services

- Medical Device Software Development

- Healthcare Mobile App Development Services

- Patient Portal Development Services

- Practice Management Software Development

- Healthcare AI/ML Solutions

- Healthcare CRM Development

- Healthcare Data Analytics Solutions Development

- Hospital Management System Development | Custom HMS & Healthcare ERP

- Mental Health Software Development Services

- Medical Billing & RCM Software Development | Custom Healthcare Billing Solutions

- Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) Development

- Clinical Trial Management Software Development

- Pharmacy Management Software Development

- Finance & Banking Software Development

- Retail & Ecommerce

- Fintech & Trading Software Development

- Online Dating

- eLearning & LMS

- Cloud Consulting Services

- Healthcare Software Development

- Technology

- Products

- About

- Contact Us

From Harvard Hospital to Silicon Valley: Why This Doctor Traded Her Stethoscope for an AI Startup

Jenny Shao left a promising medical career to build Robyn, an AI companion that claims to understand you better than anyone else. But in a market shadowed by tragedy, can she succeed where others have failed?

Walking away from a Harvard medical residency isn’t a decision most people make lightly. The prestige, the salary trajectory, the years of training leading to that moment—it all adds up to a path that’s nearly impossible to abandon. But Jenny Shao did exactly that, driven by an observation that fundamentally changed how she viewed human connection in the modern world.

During the pandemic, while working as a physician, Shao witnessed something that went beyond the typical medical concerns about isolation. She saw the neurological impact of disconnection on her patients—the way prolonged loneliness wasn’t just an emotional problem but a physiological one. People weren’t just sad; they were suffering measurable harm from the absence of meaningful human interaction.

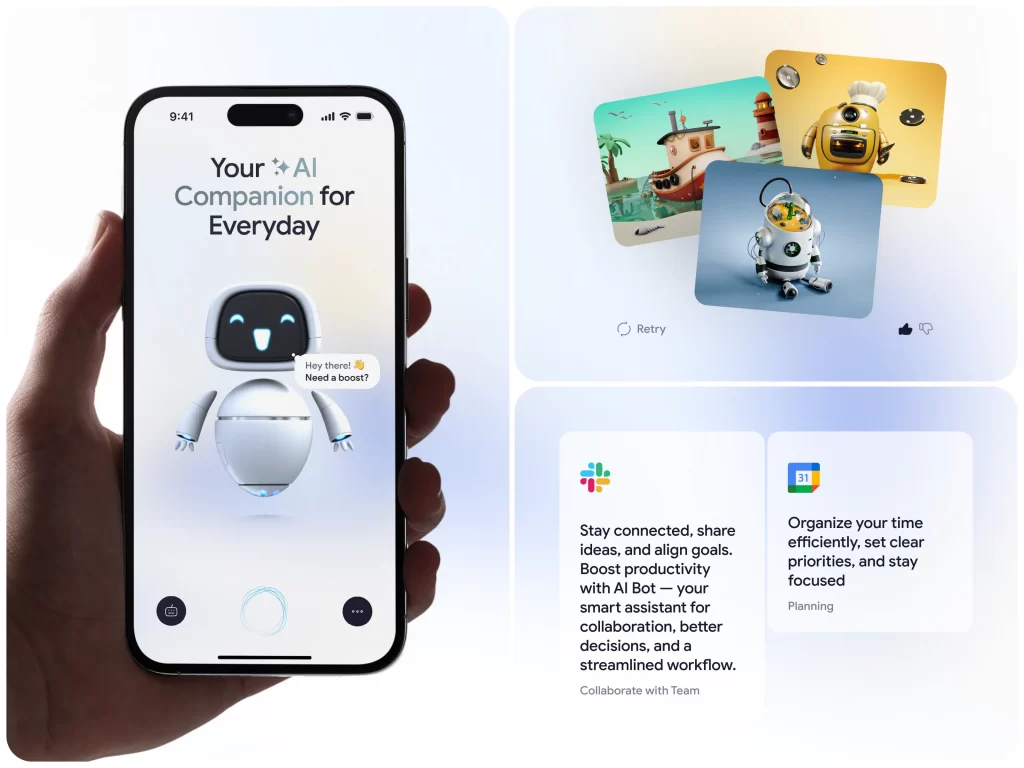

That realization led her to a conclusion that many would find counterintuitive: maybe technology, specifically AI, could help address the very disconnection that technology had partially created. The result is Robyn, an AI companion that launched today with $5.5 million in seed funding and a promise to be different from everything else in this increasingly crowded—and controversial—space.

Threading an Impossible Needle

If you’re familiar with the AI companion landscape, you probably already have questions, and they’re the right questions. This is a market category that’s simultaneously exploding in popularity and drowning in controversy.

The numbers tell one story: a study from July found that 72% of U.S. teens have used AI companion apps. These aren’t obscure tools—they’re mainstream, with apps like Character.AI, Replika, and Friend drawing millions of users seeking connection, conversation, and emotional support.

But the headlines tell a darker story. Multiple lawsuits have accused AI companion apps of playing roles in user suicides, with families alleging that the apps fostered unhealthy dependencies, failed to provide adequate crisis intervention, and in some cases, actively encouraged harmful behavior. The most recent lawsuit involves seven families suing OpenAI over ChatGPT’s alleged role in suicides and delusions.

This is the minefield Shao is walking into. She needs Robyn to be useful enough to justify its existence, engaging enough to retain users, but somehow avoid the psychological traps that have turned other apps into litigation nightmares. It’s a technical challenge, an ethical challenge, and a business challenge all rolled into one.

What Robyn Is (and Explicitly Isn’t)

Shao is adamant about positioning. Robyn is not a friendship app, despite sharing characteristics with apps that explicitly brand themselves as AI friends. It’s not a therapy app, despite addressing emotional and psychological patterns. It’s not a clinical tool, despite Shao’s medical background and the app’s sophisticated understanding of mental health.

So what is it?

“As a physician, I have seen things go badly when tech companies try to replace your doctor,” Shao explains. “Robyn is and won’t ever be a clinical replacement. It is equivalent to someone who knows you very well. Usually, their role is to support you. You can think of Robyn as your emotionally intelligent partner.”

That framing—”emotionally intelligent partner”—is doing a lot of work. It suggests intimacy without romantic overtones, support without clinical authority, understanding without judgment. Whether users will maintain that nuanced understanding, or whether they’ll anthropomorphize Robyn into something more, remains an open question.

The Science of Remembering

What sets Robyn apart, according to Shao, is how it remembers. Before launching this startup, she worked in Nobel Laureate Eric Kandel’s lab, researching human memory. Kandel won the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on memory storage in neurons, and Shao claims those insights informed how Robyn’s memory system works.

The technical details are proprietary, but the user experience is revealing. Robyn doesn’t just log conversation history like a typical chatbot. It builds what the company calls an “emotional memory system” that tracks patterns, preferences, emotional responses, and personal growth over time.

When you first launch the app (currently iOS only), the onboarding mirrors mental health and journaling apps. Robyn asks about your goals, how you react to challenges, what tone you prefer in responses. This isn’t just personality customization—it’s establishing a baseline for understanding how you think and communicate.

As conversations accumulate, Robyn generates insights about your patterns: your emotional fingerprint, attachment style, love language, growth edge, and inner critic. These aren’t just buzzwords—they’re psychological frameworks repackaged for an AI system that’s watching how you express yourself, what you avoid discussing, what you return to repeatedly.

The company even created a demo website that analyzes public X (Twitter) profiles and generates sample Robyn insights. It’s simultaneously impressive and slightly unnerving—the idea that an AI could understand personality patterns from social media posts well enough to predict how you’d interact with a companion app.

Guardrails in a Dangerous Space

Given the lawsuits plaguing this industry, Robyn’s safety measures are worth examining closely. The company claims it’s been building guardrails since Shao was the app’s only user, testing responses and refining boundaries.

The safety features include automatic crisis intervention: if users discuss self-harm, Robyn provides crisis line numbers and directions to the nearest emergency room. The app also refuses certain requests—it won’t fetch sports scores, count to 1,000, or perform tasks that standard general-purpose AI assistants handle. The message is clear: Robyn is for personal, emotional support, not utility tasks.

But are these guardrails enough? The families suing other AI companies would likely argue no safety measure is sufficient when you’re encouraging people to form emotional bonds with software. The fundamental risk isn’t whether the AI responds appropriately in a crisis—it’s whether the relationship with the AI itself becomes the crisis.

Latif Parecha, a partner at M13 (Robyn’s lead investor), acknowledges this tension: “There needs to be guardrails in place for escalation for situations where people are in real danger. Especially, as AI will be part of our lives just like our family and friends are.”

That last phrase is telling. The assumption isn’t whether AI will become a normal part of human relationships—it’s how to make that transition safely.

The Investment Thesis: Connection, Not Replacement

Robyn’s $5.5 million seed round attracted some notable names: M13 led, with participation from Google Maps co-founder Lars Rasmussen, early Canva investor Bill Tai, ex-Yahoo CFO Ken Goldman, and X.ai co-founder Christian Szegedy. The startup grew from three people at the start of the year to ten now.

Rasmussen’s investment rationale captures the broader vision: “We’re living through a massive disconnection problem. People are surrounded by technology but feel less understood than ever. Robyn tackles that head-on. It’s solving emotional disconnection, helping people reflect, recognize their own patterns, and reconnect with who they are.”

The key phrase there: “reconnect with who they are.” The thesis isn’t that Robyn replaces human connection—it’s that Robyn helps you become better at human connection by understanding yourself more clearly first.

“It’s not about therapy or replacing relationships,” Rasmussen continues. “It’s about strengthening someone’s capacity to connect—with themselves first, and then with others.”

If that sounds like therapy without calling it therapy, you’re not alone in noticing. The line between “emotional support” and “therapeutic intervention” is blurry at best, and legally, that ambiguity might be protective. Therapy apps face regulatory scrutiny and professional licensing requirements. General wellness apps do not.

The Business Model: Betting on Subscription

Unlike many AI apps that rely on freemium models or one-time purchases, Robyn is subscription-only: $19.99 per month or $199 annually. That’s comparable to therapy co-pays in some insurance plans, though still cheaper than out-of-pocket therapy sessions.

The pricing raises interesting questions about who this is for. At $240 annually, Robyn isn’t an impulse download. It’s a considered investment in a tool that promises ongoing value. The company is betting that users who pay that much will be more committed, more engaged, and hopefully, more likely to use the app in healthy ways.

It also means Robyn needs to deliver consistent value. Unlike free apps that can coast on novelty, paying subscribers will expect meaningful insights, genuine emotional support, and tangible benefits to their self-understanding and relationships.

The Anthropomorphization Problem

Perhaps the biggest challenge Robyn faces isn’t technical—it’s psychological. Humans have an almost irresistible tendency to anthropomorphize technology, especially when it responds in emotionally intelligent ways.

Even Shao’s own framing contributes to this: calling Robyn an “emotionally intelligent partner” invites users to think of it as more than software. The app’s features—remembering personal details, tracking emotional patterns, providing weekly insights—mirror what we expect from close human relationships.

The danger isn’t that people will consciously confuse Robyn with a real person. It’s that the emotional circuitry in our brains doesn’t distinguish between “real” and “simulated” empathy very well. When something responds to you with apparent understanding and care, your brain releases the same neurochemicals whether that something is human or artificial.

This is where Robyn’s medical origin story becomes both an asset and a liability. Shao’s understanding of neurology and psychology informs the product design, but it also means she knows exactly how effectively these systems can hijack human emotional needs.

The question becomes: Is that understanding being used to help people or to hook them?

The Market Reality: Loneliness Is Lucrative

We can’t discuss AI companions without acknowledging the underlying market dynamics. These apps exist because there’s a massive, growing population of people experiencing chronic loneliness. The U.S. Surgeon General has called loneliness an epidemic. Mental health services are overwhelmed, expensive, and inaccessible to many who need them.

Into that void flows technology. AI companions offer availability (24/7), affordability (compared to therapy), and accessibility (no waitlists, no insurance needed). They provide judgment-free spaces where people can express thoughts and feelings they might not share with anyone else.

Is that a bad thing? Not necessarily. The problem is we don’t yet know the long-term effects of substituting AI interaction for human connection. We don’t know whether AI companions serve as bridges to better human relationships or as comfortable alternatives that reduce motivation to pursue the harder, messier, more rewarding work of connecting with real people.

What Success Looks Like (and What Failure Costs)

If Robyn succeeds, it will need to prove several things simultaneously:

Utility: Users need to feel the app genuinely helps them understand themselves and improve their relationships. Vague platitudes won’t justify the subscription cost.

Safety: The app needs to avoid the pitfalls that led to lawsuits against competitors. This means not just having crisis hotlines, but actively preventing unhealthy dependencies.

Boundaries: Users need to maintain realistic expectations about what Robyn is and isn’t. The app can’t become a substitute for human relationships while claiming to enhance them.

Differentiation: In a crowded market, Robyn needs to offer something competitors don’t. The memory system and psychological insights might be that differentiator—or they might just be marketing.

If Robyn fails, the costs extend beyond a failed startup. Every high-profile failure in this space makes it harder for legitimate mental health technology to gain acceptance. Every lawsuit reinforces the narrative that AI companions are inherently dangerous. Every tragedy linked to these apps creates regulatory pressure that could shut down innovation in digital mental health.

The Uncomfortable Questions

As Robyn launches to the broader U.S. market, several questions linger:

Is there a version of AI companionship that’s truly healthy? Or is the entire concept fundamentally flawed, destined to create dependencies rather than foster growth?

Can guardrails really work? When an app’s entire value proposition is emotional connection, can it simultaneously prevent unhealthy emotional attachment?

Who’s responsible when things go wrong? If a user develops an unhealthy relationship with Robyn despite safety measures, is that a product failure, a user misuse issue, or something more fundamental about human-AI interaction?

What happens to the data? Robyn collects incredibly intimate information about users’ emotional patterns, relationships, and vulnerabilities. What protections exist? What happens if the company is acquired or goes bankrupt?

The Path Forward

Jenny Shao left medicine to build Robyn because she saw a problem that traditional healthcare wasn’t solving. The pandemic revealed just how fragile human connection is and how devastating its absence can be. Her solution is to use AI not as a replacement for connection but as a tool for understanding ourselves well enough to connect better with others.

It’s an ambitious vision, and the early investor enthusiasm suggests smart people think she might pull it off. But the history of this product category—the lawsuits, the controversies, the genuine harm that’s occurred—demands we approach with caution rather than optimism alone.

The truth is, we’re all participating in a massive experiment. AI companions are proliferating faster than we can study their effects. Apps like Robyn are making design choices today that will shape how millions of people experience emotional support, self-reflection, and connection.

Whether Robyn becomes a valuable tool for fostering human connection or just another cautionary tale in the AI companion saga remains to be seen. What’s certain is that the stakes are high, the path is treacherous, and the world is watching.

Recent Posts

- The Foundation Crisis: Why Hiring AI Specialists Before Data Engineers is Setting Companies Up for Failure

- ERP vs CRM vs Custom Platform: What Does Your Business Actually Need?

- The AI Enthusiasm Gap: Bridging Corporate Optimism with Public Skepticism in Enterprise AI Adoption

- The Future of AI-Powered Development: How Cursor Plans to Compete Against Tech Giants

- How Much Does Custom Software Development Cost in 2025? Real Numbers & Breakdown